PETALING JAYA, Aug 5 — One can be born, bred, and live their entire life in Malaysia but still not be granted citizenship.

This was the case for siblings Dickson Anderias, Dennis, Derita@Anita, Diana, and Jeneffer, who are in their late 40s and 50s and are still stateless in the land of their birth.

Although the Federal Constitution states that a person is a citizen by operation of law provided that one of his/her parents at the time of birth is a Malaysian or a permanent resident, or he/she was born in Malaysia and is not born a citizen of any country, none of the siblings are recognised by the government as citizens.

Coming from the indigenous Lun Bawang community, the siblings were born and bred in Long Semadoh, a village nestled in rural Lawas, northeastern Sarawak, which shares a border with the country of Brunei on one end and the Malaysian state of Sabah on the other.

Illiterate, uninformed

Dickson was born in 1966, three years after Sarawak formed the Federation of Malaysia with Malaya, North Borneo (now Sabah), and Singapore (which separated from the federation in 1965).

“Back then, we did not know much about the importance of having documents. This is probably because we lived far from town, where it took almost one week of walking through the thick jungle and logging road to get to Lawas town.

“Our parents were farmers and illiterate, and hence they did not know the importance of having a document to show ties to a country,” he said.

Despite his humble background, Dickson is bright. In the early days of the new federation, children without official documents were allowed to enrol in public school depending on the requests of parents and at the school’s discretion.

This enabled Dickson and his siblings to complete their primary education in Long Semadoh.

As he excelled academically, Dickson was accepted by a boarding school, Kolej Tun Datu Tuanku Haji Bujang, in Miri, while his siblings continued their secondary education in Lawas.

Dickson only discovered he was not a Malaysian citizen when he could not pursue his tertiary education after completing Form 6.

“I was heartbroken. While my friends were able to pursue their dreams, I was stuck in a situation that I never knew would last my entire life,” he said.

He later married Farida, who was also stateless, and had four children.

As he and his wife were not citizens, all four of their children were also born stateless.

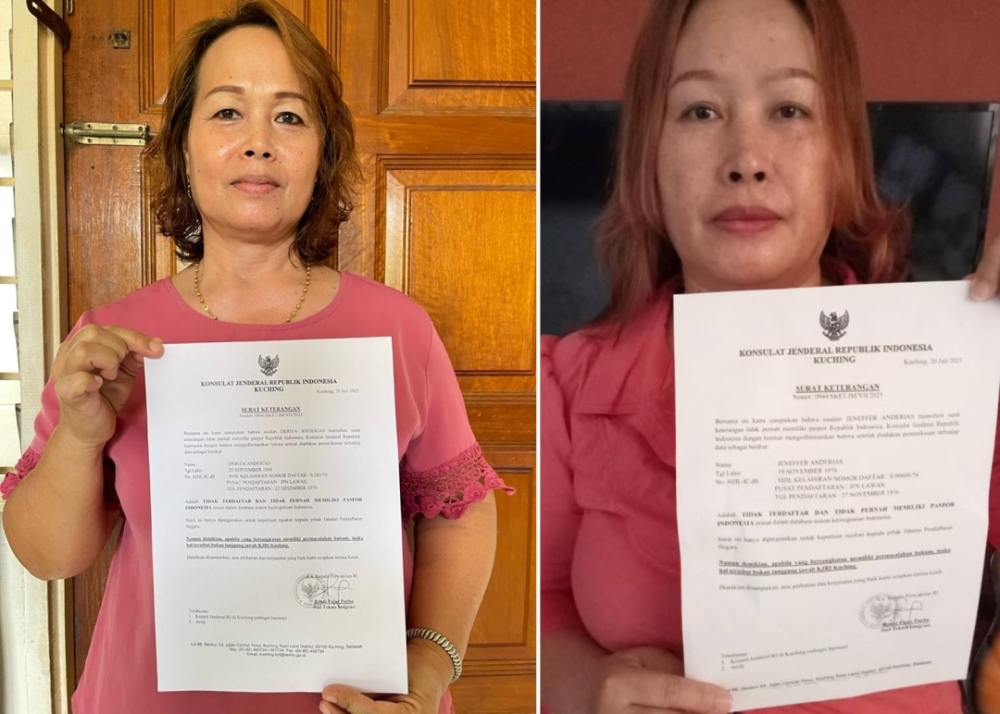

Derita (left) and Jeneffer. — The Borneo Post

Sacrifice for children

Wanting to give their children a better future, the couple made the decision to give up two of their children for adoption to relatives who had Malaysian citizenship.

Dickson said this was a decision he and his wife did not take lightly as they did not want their children to go through the hardship of growing up stateless.

Many years later, his wife finally had her citizenship application approved, which allowed her to pass her citizenship on to their two younger children.

Dickson’s grandfather Sia Murang was originally from Indonesia but married Gadung Fadin, a Lun Dayeh from Sipitang in Sabah.

After his grandparents married in Sabah, they migrated on foot to Krayan, in Kalimantan, Indonesia (border near Ba Kelalan, Malaysia), where Dickson’s father Anderias Sia, was born in 1944.

“It was in early 1965 that my father got married to my mother Ribka, whose father is a Kelabit from Pa Adang and mother from Long Midang (Indonesia), which is located at the border near Ba Kelalan (Malaysia).

“The year 1965 was during the Indonesian Confrontation. My father told us about the story of how he was requested by my mother’s brother, who at the time was a soldier, to help them spy on the movements of the Indonesian army at the border,” he said.

Dickson said his father was reluctant in the beginning, but when told this would help his wife’s family, who at the time had already moved to Bario (Malaysia), he felt the need to assist.

“However, it was not long before the Indonesians caught one of the spies but my father was lucky that he was able to flee on foot from Kalimantan with my mother to Bario.

“During the journey to escape, my mother, who was pregnant at that time, had a miscarriage. Thankfully, she was rescued by the Gurkha soldiers, who were patrolling at the border, and she was airlifted to Bario where she was reunited with my father and her family there,” he said.

In early 1966, the couple migrated on foot to Long Semadoh in Lawas, where Dickson was born later that year.

Quest begins for citizenship

For more than six decades, Anderias and Ribka had tried to apply for Malaysian citizenship.

They spent half of their lives trying to navigate the complexity of the National Registration Department’s (NRD) bureaucracy in the hopes of getting citizenship so that their children could have a better future.

After many years of trying, the couple were finally issued with a temporary resident card, now known as MyKas, which also enabled their children to apply for a similar document in 1974.

Dickson explained that he and his siblings, except for Jeneffer, were granted temporary resident status with the issuance of MyKas.

MyKas is a document issued to those born in Malaysia, but whose nationality is not known or could not be established.

These cards are issued under Rule 5(3), Rules and Regulations of the National Registration Department 1990 and need to be renewed every five years.

National news agency Bernama reported in July 2018 that there were 33,957 MyKas holders in Malaysia as of June 2018.

Even though MyKas is an identification document, it does not give its holders any citizenship rights or privileges.

“Not long after they were issued with the MyKas, the NRD then seized the documents and they were never returned,” Dickson said.

It was a race against time for Dickson’s parents as they tried to get their citizenship applications approved so that their children, who were in secondary school at the time, could pursue tertiary education.

However, they never succeed. It was only after over 40 years since their MyKas were seized that Dickson’s parents finally had their citizenship applications approved in 2018, prior to the 14th General Election.

The much-awaited approval subsequently resulted in the issuance of their Malaysian identity cards (MyKad).

“Of course, my parents were over the moon when they finally received their MyKads. We never thought the day would finally come.

“As children, we were all looking forward to changing our citizenship status to Malaysian to follow our parents,” Dickson said.

Dream realised and lost

Just four years after receiving their MyKad, Dickson’s parents were called to the NRD office in Lawas in 2022.

There, the officer seized their MyKads.

“My parents did not know how to react when that happened. They were old, illiterate, and did not know why their MyKads were seized. The officer only told them that it would be for internal investigation, and at the time, they thought that they would get their MyKads back once the investigation was completed.

“However, that was never the case. In fact, they did not even know that the seizure of their MyKads that day meant that they were losing their citizenship and the rights and privileges that comes with it,” he said.

The Borneo Post has reached out to the National Registration Department via email on the matter and is still awaiting its response.

As for his case, Dickson said that in 2005, during a renewal attempt, his MyKas was revoked.

His siblings Derita@Anita and Dennis managed to renew their MyKas for several more years until 2018.

“It has been very difficult years for my parents and all of us because we are not living together. My brother Dennis is in Sandakan, Anita@Derita and Jeneffer in Miri, while I am in Limbang.

“My other sister Diana previously lived in Kota Kinabalu in Sabah to be near the hospital as she was receiving treatment for her cancer, but she died of the illness at the end of last year,” he said.

The siblings have made repeated trips to NRD offices in Lawas, Miri, and Sandakan over the years, but lack of documents to support their applications for MyKas renewal and to apply for Malaysian citizenship have made their efforts futile.

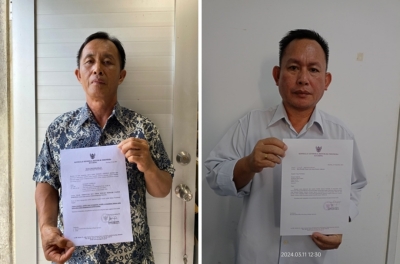

As they were deemed Indonesians, Dickson said, he and his siblings made the effort to request confirmation letters from the Indonesian Consulate in Kuching on their citizenship status.

Dickson said he received a letter dated July 20, 2023 from the Indonesian Consulate in Kuching confirming he had never held an Indonesian passport nor had he ever registered in that country’s immigration database.

“My siblings Derita@Anita, Dennis and Jeneffer had also received similar letters of confirmation from the Indonesian Consulate that they too had never held Indonesian passports nor were they ever registered in their immigration database.

“We do not know which country we actually belong to because we only know Malaysia. The Malaysian government stated that we are non-citizens in our MyKas documents, to be honest, we never regarded this land as a foreign land because we had spent all our lives here,” he said.

It was only in January this year that Dickson was able to renew his MyKas after repeated trips to the NRD office, while his siblings continue to face obstacles in renewing theirs.

As for their parents, their lifelong dream of obtaining citizenship and passing it down to their children continues to remain elusive.