The two men are at work in the overhaul workshop of Singapore’s oldest train depot, reaching into the mechanical guts of trains. With surgical precision, they take them apart, scrutinising major components and replacing faulty parts.

Mr Yahya Karthi, 62, works on 1,400kg wheelsets, while Mr Muhammad Asyik Abu Bakar, 42, handles bogies, or undercarriages, which weigh 4,300kg each – about twice as heavy as a large Sport Utility Vehicle (SUV).

Yet neither man is straining under the weight of these train parts.

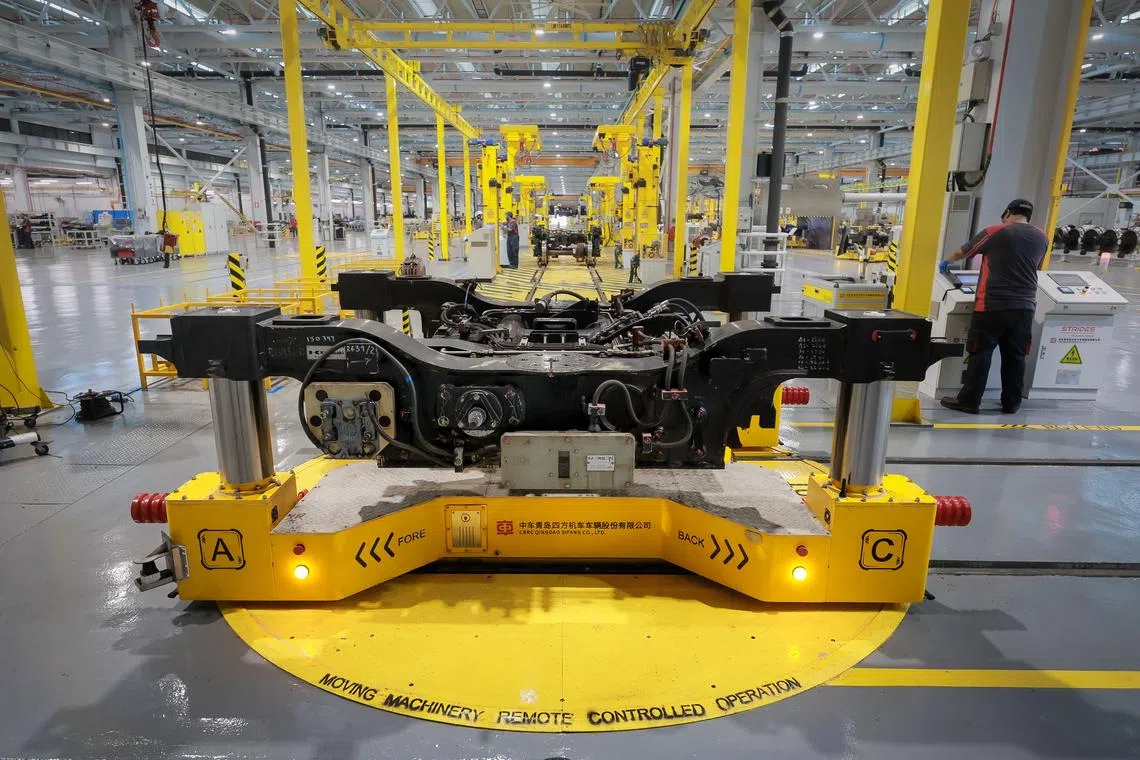

Zoom out and you understand why: All around them, in a space that spans about half a football field, are bright yellow rail-guided vehicles (RGVs) moving autonomously between workstations laden with heavy equipment. Steel structures fitted with crane hoists automatically lower wheelsets onto precise positions on bogie frames.

This is Bishan Depot, the heart of SMRT’s overhaul operations, upgraded in October 2025 after two years. The

$7 million project is named Depot 4.0

and funded by SMRT.

Senior technical officer Yahya Karthi, who works with 1,400kg wheelsets at Bishan Depot, is now supported by an autonomous system that ensures precise positioning of train parts.

PHOTO: CAROLINE CHIA

It uses technologies like automation, artificial intelligence and data analytics to improve overhaul work, says Mr Hong Dexuan, 38, director, Rolling Stock Engineering at SMRT Trains. It is the most physically demanding part of rail maintenance.

The machines do the heavy lifting. And the technical officers are grateful for the help. “I like it,” says Mr Yahya.

Bishan Depot is part of SMRT’s network of seven depots, where trains under SMRT are parked and maintained. The facilities and trains are owned by the Land Transport Authority (LTA).

Mr Yahya recalls manually repositioning and pushing heavy equipment in a messier environment. He has worked at SMRT since 1992, most recently at Tuas West Depot. In the past, different teams moved around the workshop floor to overhaul train parts.

Now, at Bishan, he has a dedicated workstation, with an autonomous system that helps him with assembling wheelsets.

“It saves us a lot of time,” says Mr Asyik, who no longer has to wait for overhead cranes to move the undercarriages of trains, called bogies. About 100 staff shared up to six cranes. RGVs now ferry equipment of up to 5,000kg to him.

The improvements do not just reduce physical strain for workers; they deliver measurable gains. Today, Bishan Depot can overhaul four six-car trains a month instead of two – with the same amount of land and less manpower.

“We can now improve our maintenance quality through the use of technology and make our systems more reliable,” says Mr Hong. Shorter overhauls also mean trains return to serve commuters faster, he adds, improving fleet availability on the network.

The need was pressing. Singapore’s MRT network has been expanding steadily since the first trains took to the tracks in 1987. “More trains means more maintenance,” says Mr Andy Chiang, 55, managing director of Strides Technologies, SMRT’s innovation and engineering arm. SMRT operates more than 350 trains across four MRT lines.

Maintenance staff at Bishan Depot share feedback on technologies and workflow improvements with SMRT Trains’ Rolling Stock Engineering director Hong Dexuan (left) and Strides Technologies’ managing director Andy Chiang (second from left).

PHOTO: CAROLINE CHIA

But land is limited, and workforce is ageing.

They had to rethink how work is done. “We asked (other public transport operators) around the world – Europe, India, China. What have they been doing?” says Mr Chiang.

“The answer was always the same: No ready-made solution existed.”

One possible reason: Perceived upfront costs, he says, as public transport operators tend to have low margins.

They widened their search and eventually partnered CRRC Qingdao Sifang to transform the depot. They were inspired by the Chinese train manufacturer’s use of technology to support its workforce, says Mr Hong.

“Technology is just an enabler,” he adds, “It is (still) about the people, the processes and how all that needs to evolve along with the use of technology.”

-

2x

Bishan Depot now overhauls four trains a month instead of two. Trains spend less time off the network for major maintenance, helping to ease congestion and keep more trains running during peak hours. -

1,000

Checks needed to ensure the driver console – which controls key functions like driving the train and opening doors – works properly. Video cameras powered by artificial intelligence now automatically verify and record these checks, cutting overhaul time from one day to half a day.

CRRC Sifang was awarded the contract by the LTA in 2023 to manufacture trains for the upcoming Cross Island Line. It is also working with SMRT on a

proof-of-concept project to upgrade trains

on the North-South and East-West Lines (NSEWL).

About 10 per cent of SMRT’s 100-strong Bishan Depot overhaul workshop team took trips lasting up to a week to Qingdao, China, in 2024. Mr Asyik, who was among them, was especially keen on the RGVs. “I knew it would make work easier for us,” he says.

Maintenance staff no longer need to use forklifts to move smaller train equipment, which can now be transported by automated guided vehicles.

PHOTO: CAROLINE CHIA

Mr Chiang likens the trip to “window-shopping”: Employees studied the systems in use and picked what they think could be adapted to their workflows. These were shortlisted and discussed over six months among the wider teams back in Singapore.

The renovation portion of the upgrade took a year, alongside ongoing maintenance work. Trains still had to run, be maintained and repaired. It was tough, says Mr Asyik. “Every two to three months we had to shift (our equipment), and we worked with minimal space.”

He took it in stride though, comparing it to home renovation. “The space is ours. This is like my second house.”

Mr Yahya, who has been working at SMRT since 1992, was initially uncertain about the changes at Bishan Depot. Now, he welcomes the support that technology provides.

PHOTO: CAROLINE CHIA

For Mr Yahya, who has spent more than three decades doing manual overhaul work, the changes were initially met with uncertainty. That has since given way to confidence, he says.

His three children, aged between 30 and 25, used to worry about their 62-year-old father working with heavy equipment. They were reassured after he told them about the changes.

With the physical strain reduced, he sees no reason to stop. “I am happy,” he says, “I will continue to work as long as I can.”

SMRT partnered Chinese train manufacturer CRRC Qingdao Sifang to revamp the overhaul workshop at Bishan Depot. The two-year project, named Depot 4.0, uses automation, artificial intelligence and data analytics to boost productivity and improve maintenance quality.

Built in 1986, Bishan Depot originally serviced only North-South Line trains. The overhaul workshop is where major train parts are removed, inspected and replaced.

Today, all North-South and East-West Line (NSEWL) overhauls are carried out at Bishan Depot, freeing up Tuas West Depot for other maintenance activities.

Here’s how the Depot 4.0 project made work…

ST PHOTO: GAVIN FOO

-

Rail-guided vehicles (above), or RGVs, autonomously move bulky train parts, such as 4,300kg bogies, or undercarriages, between workstations, removing the need for workers to manually reposition heavy equipment.

-

Train parts like bogie frames and wheelsets are automatically separated and reassembled at a dedicated station. The system communicates with RGVs to ensure precise positioning.

-

Smaller equipment like traction motors are transported by automated guided vehicles that can carry up to 1,000kg. Workers assign destinations by scanning a QR code on a handheld device.

PHOTO: CMG

-

The Maintenance Information Management System (MIMS) helps maintenance planners – now centralised at the Rolling Stock Maintenance Hub (above) – plan, track, monitor and analyse maintenance activities in real time.

-

Using artificial intelligence, it studies past records and staff qualifications to match the right people and resources to each task, maximising efficiency and quality.

PHOTO: CAROLINE CHIA

-

Traditional wrenches, which are used to tighten nuts and bolts on train components, required workers to listen for a click to know when to stop. Tightened too tight and the bolt may break; too loose and it may fall off. Torque (tightening force) values were recorded manually.

-

These have been replaced with digital wrenches (above) equipped with sensors to provide real-time readings and alerts, ensuring parts are tightened to exact specifications.

-

The data is automatically recorded and sent to MIMS for analysis and reliability forecasting.

This article was produced in partnership with SMRT.