While Li did not lose money, she said the mental anguish she experienced from being interrogated was harrowing and wanted authorities to do more to clamp down on such activity.

“What ends up happening is that the scammers tend to come up with a series of scams. So, every few weeks or so, you will see new types of scams. Once a scam is [intercepted] by the police, they start a new one,” said Radish Singh, EY Asean Financial Services Risk Management Leader.

“They plan a series of them, tens of them.”

Cybercrimes in Asia-Pacific have intensified. An IBM report earlier this year said the region faced the most cyberattacks in 2022 for the second consecutive year, accounting for 31 per cent of all incidents worldwide.

On individual scams, the Global Anti-Scam Alliance (GASA) last year said more than US$1 trillion was lost to scams globally. In Asia, the number of attempted scams has risen by about 30 per cent a year since 2020.

Malaysia arrests 7 Japanese men suspected of phone scam operation

Malaysia arrests 7 Japanese men suspected of phone scam operation

Risk solutions company LexisNexis said in a recent analysis that the scam “attack rate” in the Asia-Pacific was “well above” the global average.

There has been an uptick in scam activities in Southeast Asia, mostly through scam calls and text messages, while digital platforms such as social media, instant messaging apps, forums, e-commerce sites and digital advertisements are becoming hotbeds for scam activities, GASA said.

Types of crimes

Common scams in the Asia-Pacific region included fake demands for payments to traffic fines, fake court summons, non-existent investment schemes, love scams, fake job scams, and those involving “officials” like the ones experienced by Li, Singh said.

Outside these set-ups, scammers tried their hand at gaining access to private information on phones and personal computers by ringing victims randomly, she said.

“The key thing is not to give them any form of access, whether through a conversation or otherwise, just block them immediately,” Singh said.

Many scammers also used technology to impersonate real-life influencers or famous people in videos or advertisements to lure victims into a scam such as an investment scheme, she added.

Some scammers impersonated business suppliers offering services for a deposit paid to a seemingly legitimate bank accoun, Singh said, and warned against discarding documents with personal information in public places as there had been known instances where criminals had “hovered” around rubbish bins.

LexisNexis Risk Solutions director of fraud and identity for Asia-Pacific Thanh Tai Vo told This Week in Asia that “password reset” had become a common way for scammers in the region to gain access to a victim’s funds in a bank account.

Through phishing – social engineering used to steal personal data – criminals directed a victim to reset their password on a fake website, Thanh said, adding that using two-factor authentication was one way to combat this problem.

Once accounts had been taken over, aside from taking money from that account, criminals would create new beneficiary accounts used to launder money, he added.

Small amounts would be deposited across a vast number of these accounts and withdrawn at ATMs using “money mules”, or people hired by criminals. This can happen quickly from a few minutes to days, but well before the victim becomes aware, according to Thanh.

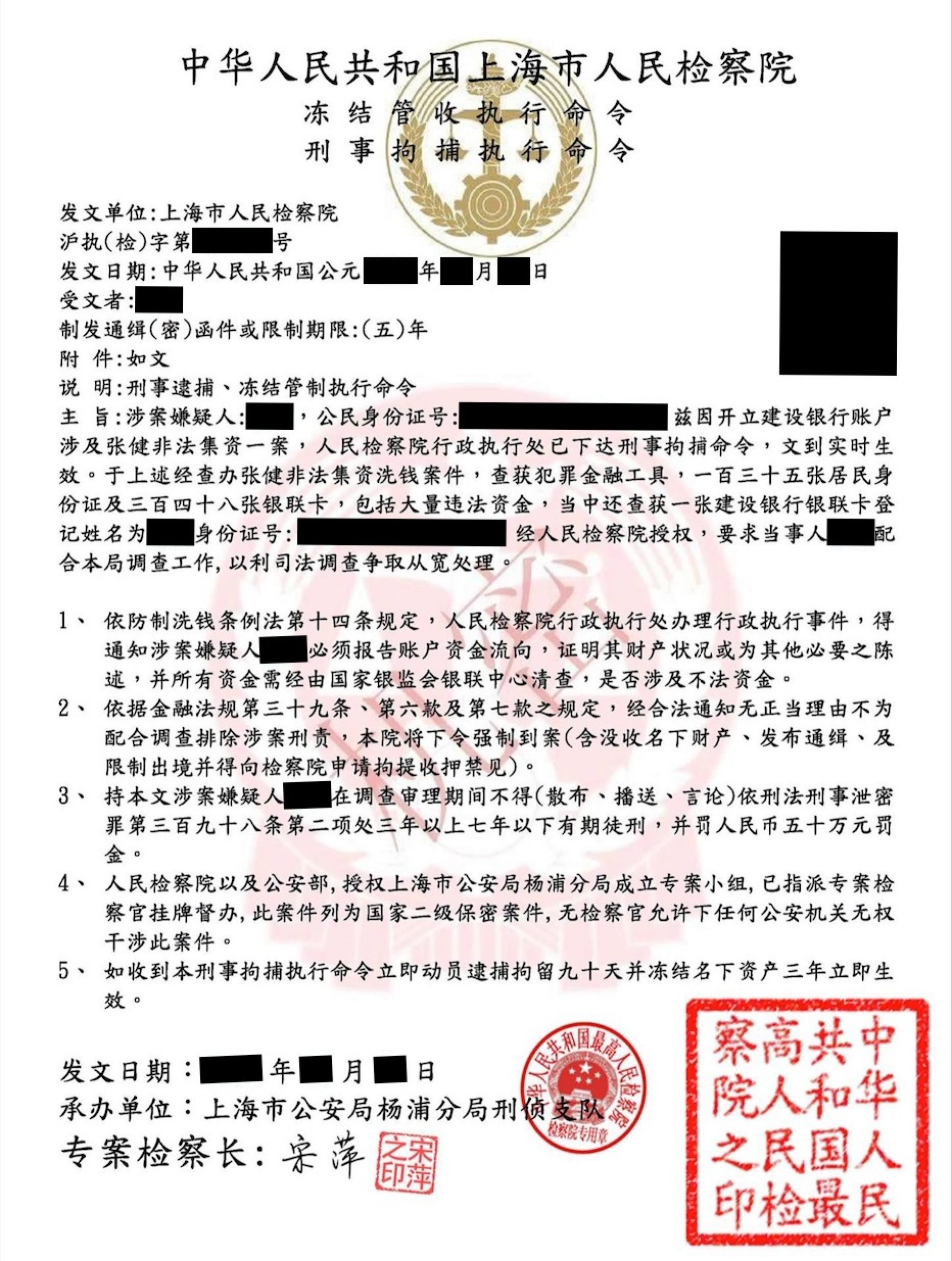

Asia’s scam crisis: fake IDs, bank letters, sob stories among ‘big red flags’

Asia’s scam crisis: fake IDs, bank letters, sob stories among ‘big red flags’

To gain victim credentials, scammers could also pretend to be bank officers asking for details so accounts could be “unlocked”, he added.

“When you receive a seemingly innocuous call that ends abruptly, and you wonder what was the point of that? It could be bad actors capturing your voice … for the purpose of then being able to train an AI-agent to produce a deep fake,” Peckman said.

“These are the ones that security professionals get concerned about, when [criminals] are simply trying to prompt you to just talk … I’ve seen some of these deep fakes to affect fraud.”

Peckman said most cybercrimes still tended to involve a human element, and cited examples in corporate cybercrimes where bad actors profile potential victims such as finance and technology officers and even CEOs using open source information to trick them into giving up data or access to systems.

On Wednesday, Aon released new data showing cyberattacks including ransomware had leapfrogged economic slowdown and reputational damage as the biggest risk faced by Asia-Pacific businesses.

The proliferation of e-commerce driven by online and mobile apps, often tied to other financial services through an interface, offers a fertile ground for fraudsters to gain access through the apps and into bank accounts, LexisNexis said.

The pandemic has triggered a surge of these e-commerce activities and therefore cybercrimes, LexisNexis’ Thanh added.

The WEF said many businesses in Asia-Pacific had rushed to adopt new technologies and digital platforms, “often without adequately securing them, leaving vulnerabilities ripe for exploitation”.

“This increased digitisation has expanded the attack surface for cybercriminals,” it said.

Prevention

Constant vigilance against scams and attacks is the best measure against cybercriminals who are often several years ahead on the digital frontier, Peckman says.

In the region, and globally, governments and businesses have stepped up efforts to protect themselves and consumers by broadcasting regular warnings and setting task forces.

In businesswoman Li’s case, New Zealand’s immigration has warned on its website about the growing number of immigration phone scams. Earlier this month, New Zealand’s National Cyber Security Centre said the number of financially motivated cyber activities had hit a new high.

Singapore cracks down on digital scams in latest law targeting online crimes

Singapore cracks down on digital scams in latest law targeting online crimes

On Wednesday, Australia released a new national cybercrime strategy pledging just under A$600 million (US$394 million) in additional funding to combat cyberattacks. Last year, major data breaches led to the misuse of personal data and millions lost by Australians.

Businesses have taken out insurances to protect their companies against financial and reputational damage caused by cybercrimes, but such products for individuals are still nascent, Peckman said, adding that governments such as the US were starting to consider “backstops” – financial protection or aid to stabilise an economy in the event of a cybercrime event.