During the Japan-US Security Consultative Committee, known as the “2+2” security talks on July 28, Washington and Tokyo agreed to further bolster military cooperation by upgrading the command and control of American forces in the East Asian country.

In Southeast Asia, Blinken paid his respects to Vietnam Communist Party chief Nguyen Phu Trong, who died on July 19, while in Laos he attended the Asean Regional Forum where he criticised Beijing’s “escalating and unlawful actions” in the South China Sea.

In Singapore, Blinken said at a dialogue that the US would remain engaged with the world regardless who became president in the November election, and defended Washington’s trade policies against China as part of a plan to ensure fair competition and protect national security.

Tan of RSIS said Asian leaders would have wanted Blinken to speak on how the US intended to counter China, and how that policy would affect the region.

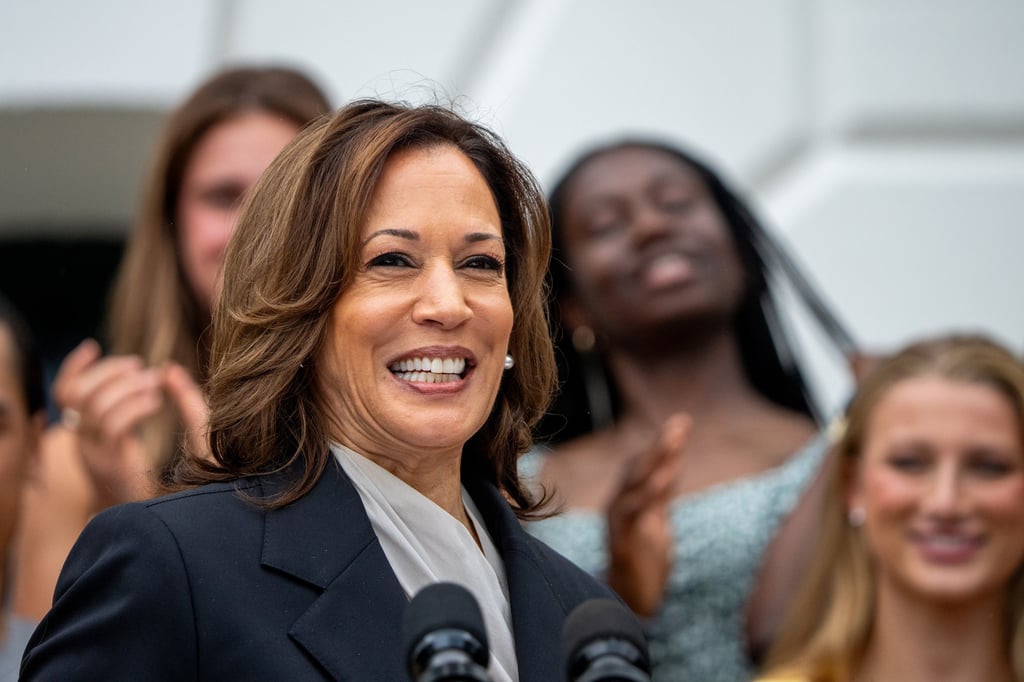

“Apart from China, Asian leaders would have pushed him to say how the US will continue to engage with the rest of Asia as a good in itself,” Tan said, adding that Blinken could have touched on what a potential Harris administration might mean for the region.

Should Harris become president, Tan said it would be worth paying attention to her current Deputy National Security Adviser Rebecca Lissner, whose ideas on the need for America to “de-risk” itself from China “could inform Harris’ China policy”.

Lissner’s ideas on the need to keep the global commons free, open and accessible are also worth looking into, according to Tan, alongside her views on the importance of the US as rule-setter rather than rule-taker.

Mark S. Cogan, associate professor of peace and conflict studies at Japan’s Kansai Gaidai University, said it was in Laos that Blinken expressed his criticism over China’s “destabilising actions” in the South China Sea.

“The location of which is strategic as there is an urgency among neighbouring states on how to manage China’s aggressive presence in their own backyard,” Cogan said.

Blinken’s visit as a whole was also “to move Southeast Asian partners closer towards a more assertive or proactive posture towards China in the South China Sea”, Cogan noted.

“The not-so-subtle message to Vietnam was that American resolve in the region is in line with Hanoi’s recent diplomatic complaints about the Hai Yang research vessel,” he said, referring to the Chinese vessel sailing around Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone in June.

Noting that what was made public versus what was discussed in private were often two different things, Cogan said it was likely that continuity of foreign policy was also on the agenda.

“I am sure that the US had circulated the message that Harris’ defiant rebuke of China during her Singapore trip a few years ago would be central to policy going forward,” Cogan said.

During a week-long visit through Southeast Asia in 2021, Harris delivered a sharp rebuke in Singapore of China for its incursions in the South China Sea, warning that Beijing’s actions amounted to “coercion” and “intimidation”, and affirming that Washington would support its allies in the region.

“This trip is not just about military aid or a contrast with China,” Cogan said, noting that it was also about foreign policy continuity.

“The rivalry is bilateral, [but] there is little corresponding criticism of [China]. Perhaps such behaviour is simply because it is easy and cheap to criticise Washington and not have to worry about costs, in contrast to Beijing,” Chong added.