“We will have to experiment, discover fresh solutions and blaze new paths. There will be voices that doubt our ability to go further. This scepticism has been with us since the beginning.”

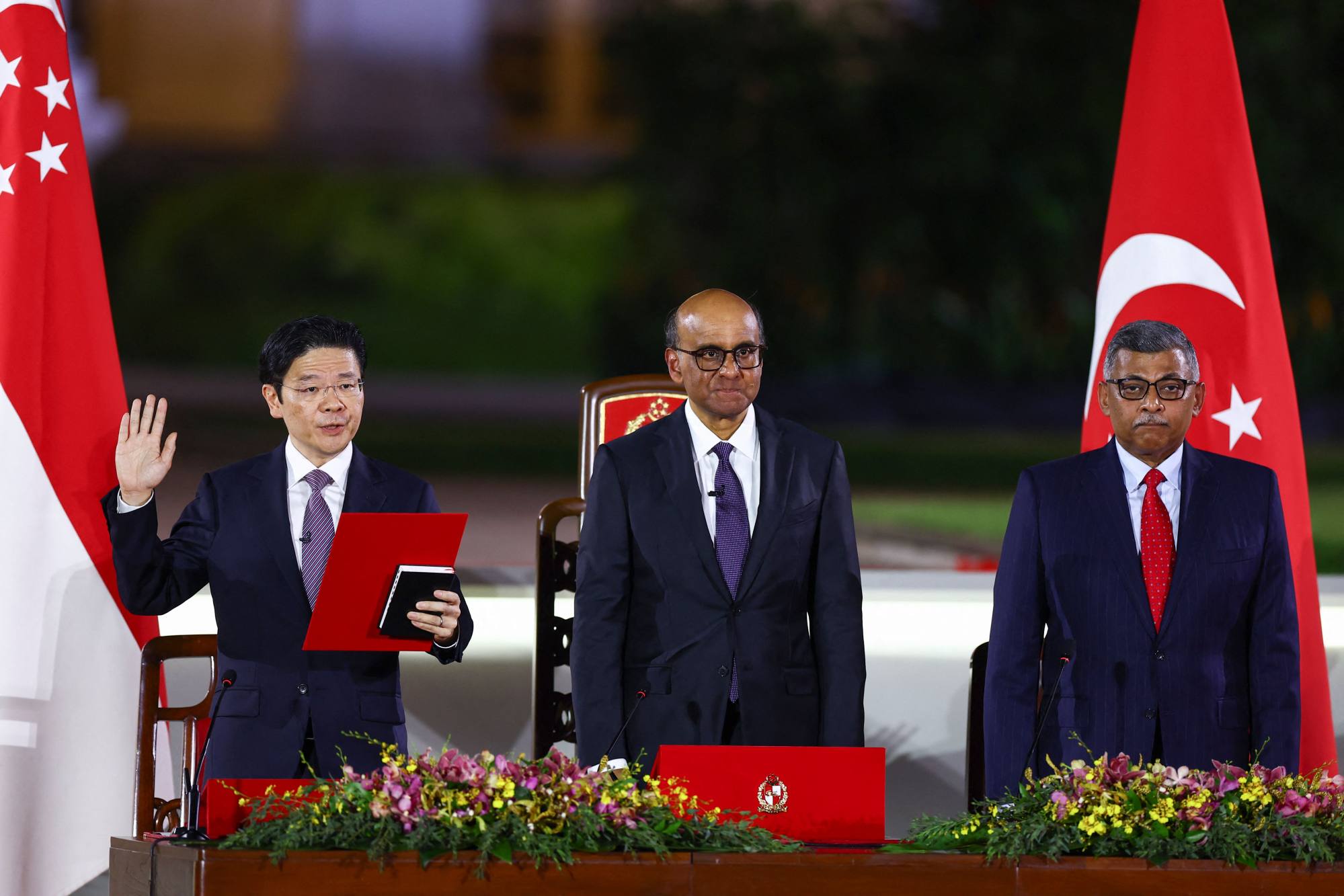

A former government economist, Wong, 51, took the baton from Lee Hsien Loong, 72, who stepped down after two decades in office. Lee’s resignation from the post marked the first time in the country’s post-independence history that no member of the Lee family is helming the office or waiting in the wings. Lee remains in Wong’s cabinet as a senior minister.

His father, the late Lee Kuan Yew, was Singapore’s founding prime minister who led the country for 31 years and transformed the city from a third-world outpost to a first-world hub.

Like most of his colleagues who make up the ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) so-called fourth-generation leadership, or the 4G locally, Wong is the first Singapore prime minister born in the country’s post-independence years.

The PAP has governed Singapore for an uninterrupted 65 years since 1959, priding itself on running a meritocratic, multiracial system that is opposed to corruption.

Acknowledging these values and the importance of good leadership, political stability and long-term planning, Wong made clear his team’s style of governing, even as he had previously pledged continuity, would, however, be different.

“We will lead in our own way. We will continue to think boldly and to think far. We know that there is still much more to do.”

Giving Singaporeans the first official sampling of his priorities, Wong had his eyes firmly set not just on the challenges at home but also abroad.

Singapore was grappling with a “messier, riskier and more violent world”, he said, noting how the great powers were competing to shape a new, yet undefined global order and with the transition riddled by geopolitical tensions, protectionism and rampant nationalism.

“We hope for stable US-China relations and will continue engaging both powers, even as issues inevitably arise between them. We will strengthen our partnerships, near and far; and advance Singapore’s interests, so as to better shape outcomes for ourselves as well as the world,” he said.

Thus far, analysts have noted that Wong’s foreign policy touchstones will continue prioritising stability, enhancing military capabilities, and economic growth.

Earlier this week, he said he would continue to serve as finance minister after becoming the PM, while Gan Kim Yong, who co-chaired the republic’s multi-ministry Covid task force, would become deputy prime minister, alongside Heng Swee Keat.

This was to “avoid any disruptions”, he said, adding that ministers would retain their present roles until the end of the term. An election is due to be held by November 2025 and it will be his first leading the PAP.

In a letter to President Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Lee wrote that though he planned to cede power at 70, “this timetable was disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic”.

“After the pandemic, we carried out a process to choose my successor … now, two years on, he is ready to lead Singapore,” he wrote of Wong.

In his swearing-in speech, Wong thanked Lee profusely, describing him as having “devoted every measure of his being to the service of our country and people”.

“Mr Lee spoke often of the need to keep Singapore exceptional. He was exceptional himself – in his devotion, his selflessness, and his dedication to serve,” he said.

Lee oversaw the country’s transformation from a trading and manufacturing port to an innovation and entrepreneurship hub, and weathered through major crises such as the 2008-09 financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Singapore’s gross domestic product surged from S$194 billion (US$142 billion) in that year to more than S$600 billion (US$439 billion) last year.

The median gross monthly income of Singapore residents has also more than doubled from some S$2,300 to S$5,100, while the Gini coefficient – a measurement of inequality – after government transfers and taxes dipped from 0.42 to 0.37.

At Wednesday’s ceremony, Wong made an appeal to younger Singaporeans in their 30s and 40s to join the ruling party as it prepares to head to the polls.

“Help me to provide Singaporeans with the government they deserve. Let us make a difference, and serve our nation together.”

To rousing applause by the country’s who’s who and a cross-section of Singaporeans from all walks of life, Wong concluded his speech: “My mission is clear: to continue to defy the odds and to sustain this miracle called Singapore.”

At Yew Tee, Wong’s constituency, an excited crowd had gathered to watch the live telecast of the swearing-in, with supporters erupting in cheers after a host revealed the newly minted prime minister would be paying a visit.

About continuity, not radical change

While Wong’s speech was largely predictable, it was “a nice nod to younger Singaporeans’ aspirations in terms of looking beyond material welfare”, said Walid Jumblatt Abdullah, an assistant professor specialising in political science at Nanyang Technological University.

The analyst added that the focus was on continuity instead of radical change.

Wong, like other 4G members of the PAP, would face a trial by fire on issues beyond economic and social policy as “none of them have led a ministry that’s in charge of foreign policy, security or defence, and that is an area that they will have to make up”, noted Chong Ja Ian, associate professor of political science at the National University of Singapore.

In a documentary aired on national television soon after, Wong spoke of his life story running through the arc of the “miracle” of the past six decades since independence.

“My life spanned Singapore’s stunning, rapid development,” he said, as he recalled his growing up years as the son of a teacher and a sales executive living in a public housing estate and going to a neighbourhood school. He went to the United States to study economics on a government scholarship.

“My story is a story of possibilities,” said Wong, seen as a dark horse contender for the top job who only rose to the top in 2022 after a stellar performance managing the country’s pandemic response. He was chosen by 14 out of 19 peers, after appointed successor Heng ruled himself out.

In an interview published by local media this week, Wong said it was “not unimaginable for two or maybe three opposition parties to come together, form a coalition and run the government” at the next election if the PAP could not deliver.

“This is the reality of our political situation today. It is no longer a dominant system, one-party system,” he said.

As the party heads into the next general election, rising cost of living, the goods and services tax hike and housing are seen as several hot button issues while a corruption trial of one of the ruling party’s former stalwarts looms.

The PAP has won 14 general elections. The current parliament has eight opposition MPs among its 86 elected members.